|

I have been writing fiction for quite a while, and if I counted my childhood, where I wrote small stories in folded sheets of paper and tried to sell them to my parents, it would be even longer. Even in all that time, besides the stories themselves, I had never created anything — until I wrote my first 100 x 100 micro novel (which I have on multiple occasions referred to as a “Novel in 100-Word Stories” in an effort to make it easier for the reading public to understand the concept).

It started as a “what if,” like many other curiosities do. What if I wrote the arc of a novel in 100 chapters containing exactly 100 words each? I had written collections of 100-word stories before, something that has roots that go back to Paul Strohm’s Sportin’ Jack, followed by Grant Faulkner’s Fissures, and while the 100-word story as a form has taken off and is enjoyed by writers across the world, no one had strung them together into a larger story until I published A Burst of Gray. Shortly afterwards, I began to challenge my creative writing students, as well as other writers, to try their hands at the form. Few took me up on it, but eventually one of my students locked into the form and is working on what I sense will be an amazing book that only she could write. Should she ever publish it, I will be her biggest fan. As of this date, though, only one writer, whom I met through my wife, has successfully created a 100 x 100 micro book (nonfiction, as opposed to fiction) and that is Glenn Hadley, who wrote a wonderful book about how he met his wife and the life they built together titled An Evolving Love Story of 100-Word Chapters: Volume 1. I highly recommend it for those of you who would love to see an excellent example of the form being used to write a memoir. But how in the world can you (1) write a full story using 100-word chapters, and (2) have the audacity to call anything that amounts to 10,000 words a novel? Let’s start with the latter. I realize others are prepared to die on this hill, but to me a novel is not necessarily dictated by length; it is dictated by development. And if you’d like to dig a little deeper, you might find that many “novels” are in fact not even novels; they are novellas. And to compound that, many of those books that are technically novels are really bloated novellas. In short, I think we waste a lot of time relying on definitions like this, but if you are a stickler for the 50,000+ word definition, then feel free to refer to the 100 x 100 micro novel as a novella or novelette, but do note that I say “micro” novel, which emphasizes a tremendous amount of distillation and brevity. So I will happily use this oxymoron until someone can come up with something better. Now, for the former question. If you think about the narrative arc of a story — and consider that 100 chapters is a nice, clean number to gage percentages — then you can sense where a story should be 75 chapters in or where a hook should be in the earlier part of a book. It’s not rocket science; it’s measured storytelling. Where it gets interesting, though, is how you select the right scenes and arrange them so that the chapters can breathe like chapters and move the narrative forward. Writing a 100 x 100 micro novel (or a 50 x 50 micro novella) is all about carefully curating the moments that are essential to the larger story arc. Dialogue and descriptions must be more carefully chosen. The desire to engage in insane bouts of literary logorrhea must be controlled. And like any other form of microfiction, you must feel comfortable implying things, as opposed to saying them explicitly. One last question: how is this different from a “flash novel” (a term coined by Nancy Stohlman) or a “novella-in-flash” (a term that has flourished throughout the U.K.)? I could talk about a number of things, but it would only obfuscate the one key thing that matters: the 100 x 100 micro novel is built around a rigid word count and structure. Every single book written like this (sans the chapter titles) is exactly 10,000 words. The other forms, while challenging in their own ways, don’t have exact word counts or lengths. As of this writing, I have written three of these types of books: A Burst of Gray, Black Marker, and GloKat and the Art of Timing. Will I write more? Definitely. I have ideas for novels that never got completed to my satisfaction in the longer form that I feel will work well with this new structure. If, however, you’re writing the next Don Quixote, you might need more than 100 chapters to pull that off. (I say this in jest, but I might very well undertake a task like this myself, just to see if I might be able to entertain Lydia Davis for a brief moment.) If you have dabbled in drabbles (100-word stories), I invite you to challenge yourself and write a 100 x 100 micro novel, as it is feeling kind of lonely out here right now. :) Happy writing!

0 Comments

My daughter was born two years after I published my first book, and a few years later, she asked me, “Daddy, when are you going to write a book I can read?”

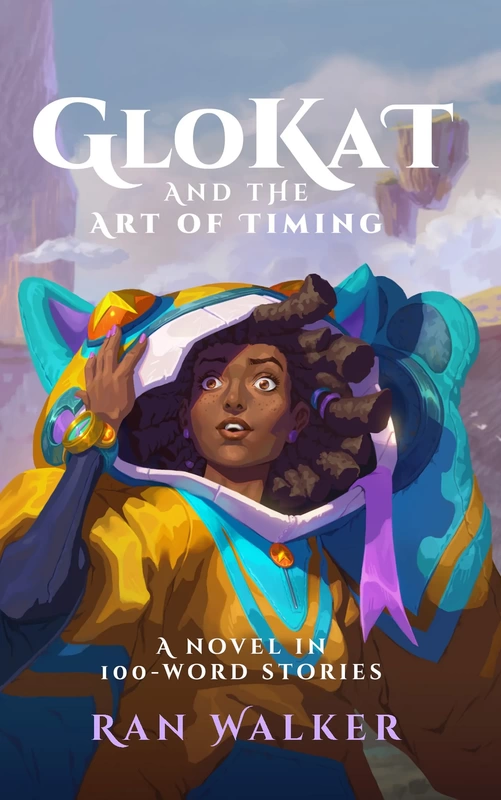

I know many children have probably asked their writer-parents to create something for them, but I will say this from experience: if you are not already inclined to write for children, trying to do so requires Herculean effort. My first two novels were romantic comedies. My third was a blues triptych. I have had stories published in horror and erotic anthologies. In other words, I know my way around polite (and impolite) language. But even in all of that, I struggled to write something my daughter could read. So it became a bucket list item. I would write a story for her (while she was still a kid), and it would be magical in the way that the books I read as a kid were. Still, for the life of me, I didn’t have any ideas about what to write. The thought of writing for my daughter froze me in my tracks. Then something quite serendipitous happened in early 2022. Out of the blue, I received an email from Matthew Garcia-Dunn, the Chief Narrative Officer at the video game startup Worldspark Studios. He informed me that not only had he read my book A Burst of Gray: A Novel in 100-Word Stories, he’d made it required reading for his company. An email with news that good quickly made me think I was on the receiving end of a con, but I still followed up with him. I figured, being a lawyer, that I would be able to sniff out anything suspicious, if it came to that. What did happen, however, was a wonderful conversation about creating characters in different universes and an invitation to come work at the company helping to develop the lore around the game. Worldspark, unlike other gaming companies, wanted to present positive characters and storylines, devoid of violence and hyper-sexualization. In short, they wanted to create fun games and stories that would appeal to both kids and adults alike. Hopepunk, if you will. After reviewing the amazing list of characters the narrative team had already created, I homed in on GloKat (brilliantly named by Emma Coats). Seeing this vibrant Black girl in her yellow and blue cat-like anime parka immediately put me in the mindset of my own daughter, and I knew I wanted to be the one to help tell that character’s story. Much to Worldspark’s credit, they saw the value in publishing a book around one of their key characters, and that began the process of working on the book with the Narrative team, Matthew Garcia-Dunn and Abigail Harvey. The team allowed me to write the book I had in me to write, which was surprising, as I had been struggling to create stories my daughter could read. Now, suddenly, with a team of people completely invested in these characters, I found that something inside of me “sparked,” and I began composing this book using a form I had pioneered with A Burst of Gray: writing a 100x100 micro novel, which is essentially a novel written in 100 chapters containing 100 words each. The goal was to create something in the realm of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, except through the lens of Black Girl Magic and Afrofuturism. I would use other characters from the gaming universe, and write a story that would allow fans of the game, as well as those who were purely interested in the story, to enjoy the story. Even more, I saw in this book something my own daughter could read — better yet, something I would be both proud and honored for her to read. So that’s what I did. And GloKat and the Art of Timing: A Novel in 100-Word Stories was born. A book is only as good as its editors, though, and having both Matthew and Abigail believing in the project and pointing out areas that could strengthen the book made the process (not just the writing itself) pleasantly memorable. Even more, the larger Worldspark team was enormously supportive, especially Chandler Thomlison, the company’s founder and CEO. Finally, Alvin Lee, the legendary comic book artist and principal artist at Worldspark, designed one of the most beautiful, vibrant covers I could have ever imagined. When everything was completed and published, I stared in awe at this small book, this representation of something I had always wanted to write. I had finally written a story about a Black girl on a quest to find her father, while simultaneously seeking a way to save her Earth from becoming completely uninhabitable. It literally gave me goosebumps to hand this book to my daughter. She read it in a single day and loved it! Since then, many readers have journeyed with GloKat through Sparkadia. (Have you?) My daughter’s signed copy now sits on her bookshelf, next to other books she’s read. This one is special, though. It is the only one there that was written by her father, the only book among the group that was written especially for her. Shortly after I finished my first collection of 100-word stories, Keep It 100, I began considering if I could write a novel using 100–word stories/chapters. I had never seen it done before, although I was fairly familiar with the novella-in-flash and the flash novel. Still, this micro-novel, which, honestly, doesn’t seem to completely capture the essence of using a singular, word-specific form, was not something I was seeing in the wild very often. Sure, there were The House on Mango Street, We the Animals, The Department of Speculation, and other novels that used brief chapters, but those books did not have chapters of the exact same length.

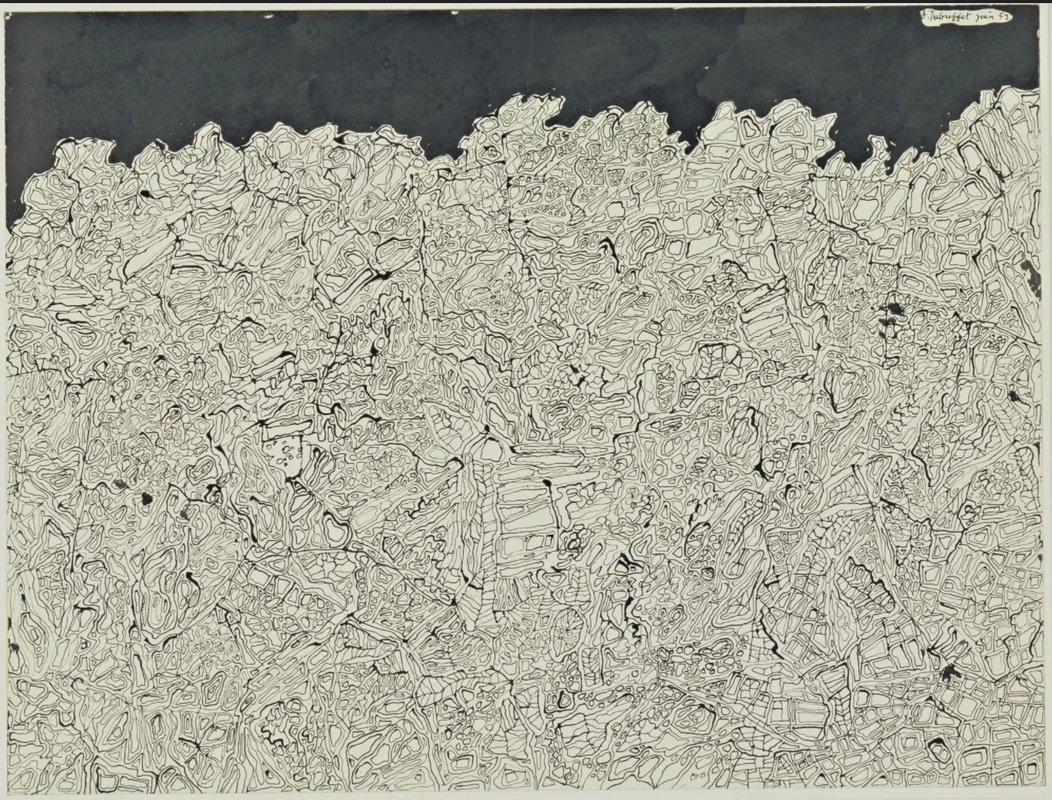

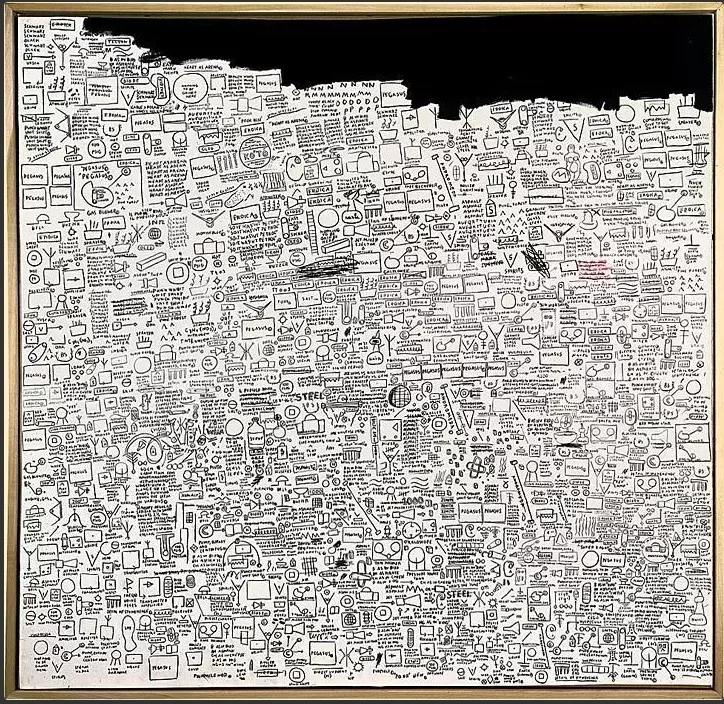

The math was easy: 100 100-word stories was 10,000 words. How could a person really keep a straight face while calling that a novel? As I began to write the book, though, I noticed that many of the same ideas and structures I had employed on earlier novels came into play here, as well. Once I completed it and read it, I realized that it very much felt like a novel. It’s just that it was distilled, with space for the reader to interact mentally with the content. So I guess it is possible to write a 10,000-word novel after all. But in the words of Ian Malcolm, just because someone can do something doesn’t exactly mean that they should. To get around this, I had only to answer this question: Why would this novel form be best for this particular story? Answering this question turned out to be much easier than I had originally thought. A Burst of Gray is an unusual book all the way around. It is a story that works effectively in the 100-word story/chapter style, but it is also a work of Afrofuturism that does not rely on race as a part of the plot. It is a love story that one could easily argue is not exactly a love story. It is many things, all of which are different, but it clearly works as a “novel in 100-word stories.” In the future, I hope to see other people using this specific form for their novels. Maybe by then the phrase “A Novel In 100-Word Stories” will have been replaced by a much shorter and smoother monicker. Let me preface all of this by saying that I do not, in any way, see myself as a genius. I am just a writer, nothing more, nothing less. But like any other artist, I have found influences can make a world of difference. In a previous Medium article, I mentioned my fondness for César Aira, an Argentine novelist whose works are famously brief and idiosyncratic. I realize, with some sense of irony, that most of my readers have never read Aira, let alone heard of him. While it is not necessary to see a correlation between his work and some of my later work, it does deepen the understanding of my work a bit more. It’s like watching The Simpsons and finding a scene funny versus watching the same scene and seeing the Stanley Kubrick reference and then finding it funny on another level. I was recently rewatching the Basquiat documentary, The Radiant Child, and I realized that most people who love the artist are nearly clueless about his work. I am not attempting to diminish one’s direct reaction to seeing his work, but I want to point out that what you see on the surface is only part of what you’re actually seeing. As the film so eloquently states, Basquiat remixed other artwork from the vast international canon of art. In other words, Basquiat, like a hip hop DJ, took an idea originally expressed by someone else, then reinterpreted it, putting his own unique spin on it. Being aware of Dubuffet’s painting makes the experience of viewing Basquiat’s painting even deeper.

Likewise, J. Dilla, the late brilliant Detroit hip hop producer, was able to mine gems from his vast collection and appreciation of music from all cultures and genres. This is evident in his classic beat for Pharcyde’s “Runnin’,” a 1995 rap song that utilizes a snippet of Stan Getz and Luiz Bonfá’s “Saudade Vem Correndo,” a jazz bossanova song recorded in 1963. Sure, you could appreciate the song for what it is, but for the person who has listened to the original song, there is an added level of appreciation for how a melody can be so thoroughly transformed. (Click here to listen to this example.) Even more, one almost has to inquire as to how the artist discovered the original in the first place, when many of his counterparts don’t see themselves in an artistic conversation that extends beyond their own peer group. Over the past couple of years, much of my work has been influenced by writers from other countries, writers like Ana María Shua, César Aira, and Haruki Murakami. All of this begs the question, though: if I’m clearly operating based off a particular set of influences, how “commercial” is my work once it is filtered through my own personal and cultural lens? At this point, I would have to say that I have rather low expectations that my work will appear in print via a large publisher any time soon. Surely there are some smaller publishers out there who might care a bit more about what I’m doing. Still, I have found that certain types of work are more acceptable as having been translated from another language, as opposed to written originally in English by an African-American man. But as one of my favorite MCs, Phonte, once said, “Why rage against the machine when you can just unplug it?” Therein lies the reason I will never close the door on the notion of self-publishing my own work. I think it’s important for these stories to make it into the world, because one day in the future, a reader may come across them and appreciate them for all that they are (or were attempting to be). There have been many times since I began my career as a writer that I contemplated a complete reboot. Whether it was after recounting my dealings with traditional publishers or lamenting the direction I have gone in with my own indie publishing, I held on to the idea that I could create a pseudonym and come back one day to right the ship.

Maybe this is one of the reasons MF DOOM appealed to me. While I won’t recount the evolution of the emcee Daniel Dumile here, it is important to know that he was a man who rebuilt himself from the ashes of his former self, a guy who played by the rules, and when those rules betrayed him, he emerged as the masked supervillain to do things on his own terms. Without really thinking about it, I turned to MF DOOM hundreds of times over the years as I chose to ignore genre and write whatever I wanted to write. Sometimes just seeing the mask made me feel like anything was possible. So when I learned at the end of 2020 that Daniel Dumile a/k/a Zev Love X a/k/a MF DOOM a/k/a Viktor Vaughn a/k/a King Geedorah a/k/a The Supervillian a/k/a Metal Face had died on October 31st (and belatedly revealed to us by his wife on December 31st), it threw me into a different headspace. It forced me to take a kind of personal inventory on my own creative life, as I grieved his. MF DOOM believed in doing things his way. He believed that greatness was really out of reach and that the best an artist could do was be better than he/she/they were the day before. He believed that the work should speak for itself. He believed in collaborating with people he admired. He wasn’t afraid to take chances. He didn’t view himself as a torchbearer. He listened to music outside of his genre more than within his genre. He drew inspiration from other areas of art. In all of these things, I see myself. Part of my creative aura is inspired by Toni Morrison and Ralph Ellison, but another part of my creative aura is inspired by Jean-Michel Basquiat and MF DOOM. I view art as a dialogue, and in my case, a dialogue across various media. My books are not designed to just be in dialogue with César Aira or Lydia Davis or Henry Dumas, but also in dialogue with MF DOOM and Kara Walker and even Savion Glover. I keep the energy of these people around me, and it inspires me when I wrestle with my place in the vast and uncertain world of publishing. I haven’t ruled out using a pseudonym yet, but I am choosing to focus my energies on celebrating the lives and works of those who have inspired me up to this point. I am grateful that Daniel Dumile decided to share his gift with the world and that he gave us MF DOOM. May he rest in peace. As we grapple with the impact of Covid19, many readers are tightening their purse strings, choosing to focus their resources on basic necessities, rather than the luxury of buying new books. As a result, we are seeing numerous traditionally-published authors launching books that are met with hardly a glance, many of them with little in the way of marketing support since most bookstores are closed for the foreseeable future.

Many traditional publishers have built their economic models almost entirely around bookstores and online sales. There is, however, another option for selling books, an option worth strongly considering if you are an indie author: public libraries. In fact, rather than spend all of your time and resources targeting individual readers, it might prove wise at this point to target public libraries. First, libraries don’t cost readers anything more than the cost of a library card (and in many places library cards are free). People can still have access to your books and read them, even if their financial resources are earmarked for other essentials. As long as there are people reading and engaging with your book, there will be reviews and word of mouth working for you and your overall author brand. Next, librarians are showing greater interest in local authors. This is evident in the explosive growth of the Indie Author Project, a program launched to help state librarians curate books by indie authors in their states. Having the support of librarians also helps to stimulate word of mouth with your book. I would venture to say a librarian’s endorsement of a book might ring louder than that of a book sales associate at a book chain. Another good thing about libraries is that they have budgets to purchase books. This is not to say that you should price your book in a way that seeks to exploit this; it is merely to say that there are institutions where buying books is a part of their budgets — something not to be dismissed when many readers are cutting back on book purchases. And for those of you who have sold books to bookstores but the books were returned to your chagrin, libraries don’t typically return books. So as we continue to socially distance ourselves and wait out the storm, consider reaching out to your local library. There might be an opportunity there for you that could pay off major dividends. Roughly a year ago, I got really fascinated with an Argentinian writer named César Aira and ultimately purchased all of his work that had been translated into English (most of them by New Directions Publishing). After reading his work, listening to interviews from podcasts, and watching subtitled interviews on YouTube, I realized that much of my recent output is heavily inspired by him. In fact, upon some reflection, I can think of four big reasons he has infiltrated my creative process so thoroughly.

Earlier this year, I had the privilege of publishing a tiny novella entitled Work-In-Progress, where I paid homage to César Aira by attempting my own fuga hacia adelante work. My literary partner-in-crime, Sabin Prentis, asked me if this was a new direction (no pun intended) for me or if this was just a one-off. At this point, I’m just following my pen — and my pen tends to bend toward my influences, artists like César Aira. Something rather peculiar has been happening with my writing over the past few years. It started with me writing shorter and shorter novels. Then I became obsessed with novellas. There was a brief fascination with novelettes before I began to dive back into short stories. And that’s when it got really interesting.

To be honest, I must admit my fascination with miniatures really coalesced over the past two years. I went from poster-size art to paintings that were 5x7" and smaller. I started buying music EPs, instead of LPs. I started to appreciate and value what could be accomplished in much smaller spaces. That eventually led me past short stories into an area commonly referred to as flash fiction, which most people will say are stories told in under 1,000 words. To write flash fiction, the writer has to really zero in on the impactful part of a story and tell that part, while implying everything else. And if you think that’s a challenge, then the next part of my quest for miniaturization of literature would be even more startling: microfiction. Microfiction is a story told in three hundred words or fewer, which leads very quickly to drabbles (100-word stories) and dribbles (50-word stories). There are even people out there writing six-word stories (for which Smith magazine is best known). I’m sure most people are aware of the “For sale. Baby shoes. Never worn.” apocryphal story often attributed to Hemingway. The bottom line is a writer can get a lot of story out there with the right set of words. It seems as if everything in my creative writing universe leans toward the smallest thing, and I can’t seem to figure out how all of this happened. One might blame it on a decreasing attention span, but I think that notion belittles the art. I sense it has much more to do with the power of language to convey ideas. The very thing that is the lifeblood of poetry is the lifeblood of flash fiction and its subparts. I have written seven novels and four novellas, but I doubt I have been as creatively challenged as I am when I tackle these tiny pieces of fiction. And, thankfully, there are a plethora of places to publish them. A simple Google search reveals hundreds of possible places to submit. I’m not sure how long I will be in this space of literary miniaturism, but I’m enjoying the evolution of what’s happened so far. I imagine one day people will try to get down to one-word stories (or even no-word stories using just punctuation), and who knows, I might just try those, too. |

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed